With the searing hot talk of the Oscars taking place, we interviewed fresh newcomer in the directorial scene, Quinn Shephard.

RELATED: How Filipino Designers Envision The Oscar Nominees On The Red Carpet

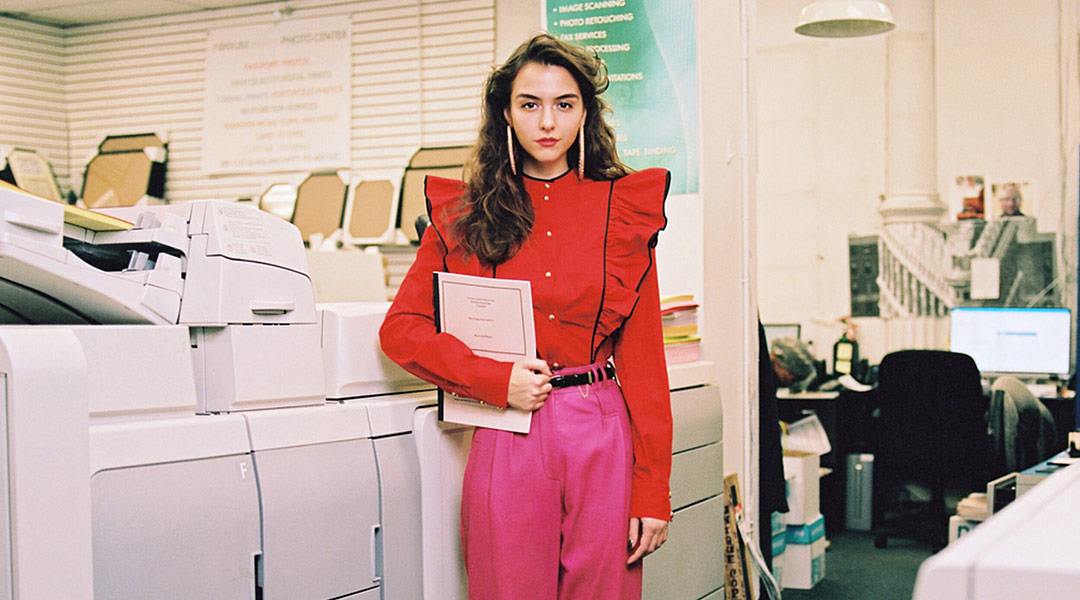

Accidentally seductive and drunk with unwarranted lust—that’s one way to describe the 2017 film Blame, at least at first glance. But Blame is more than just that; it comes with sobering realizations of consent and intricate exploration of sexual relationships between older men and young girls. Quinn started this project when she was still in high school, having finished the first draft at fifteen years old. Inspired by her own internal struggles with male affirmation, Quinn borrows rhythmic and tonal influences from 1990s American high school films and Winona Ryder classics, such as Heathers and Girl Interrupted, in Blame.

While unpolished and still plenty to improve on, Quinn is resilient, if nothing else, and continues to move fiercely forward as a director. But the lead-up to her successful debut is still your typical story of overcoming stressful circumstances all the way to the top. “The entirety of the budget of the film was actually financed by, largely my college funds and a bit by my family…We had an investor who pulled out during the shoot so, it wasn’t a choice we made going into the film,” she explains earnestly over the phone. Our call is long as she goes through the motions of her personal struggles in the making of the film. “I knew that I would rather risk everything and have the thing that mattered the most to me [which is making this film] and make that happen.”

Blame is a film wrapped in enticing aesthetics and promises of romanticized sexual encounters. But it twists these expectations and explores with delicate nuance the power dynamic that exists in age gaps between male and female relationships. While eager to move on to more new projects and explore new themes, Quinn cements Blame as the project in which she wanted to explore consent, women’s relationships with men, and the way male attention is sort of imposed on women at that young age.

Only twenty-four and still establishing herself as a competent player in the filmmaking scene, Quinn is not exempt from the downsides of trying to make it in an extremely chance-driven industry. “You’re trading, I think, the experience of having something so incredible happen for you, but at the flip side of that you also have to learn to process rejection, stress, and you know, waiting for other people’s approval.”

Quinn is determined to use her voice to tell authentic stories of women, of herself, and of female-driven queer stories in an industry that is so lacking in diversity. Furthermore, she is not afraid to call out the Hollywood bias that serves as a backbone for the award season snub against female directors such as Greta Gerwig and Alma Har’el. “There’s uproar every year about the fact that there is a lack of equality, and then every year we just fail to have that equality,” she debates. “I think it is really odd to me when things happen where, like, for instance, Little Women, the film is nominated for Best Feature but not for Best Director. It does sometimes feel like almost like a direct snub, like—they’re just so unwilling to nominate a woman.”

Brave as she is, she slams passionately the media biases that have longed plagued Hollywood. When asked about creating a space within the industry to help promote diversity without the heavy lenses of criticism for women and minority directors, this is what she had to say: “I do think that all films should be criticized with equality…I think it’s more though that if you’re going to criticize films with equality, you need to criticize films with equality. And right now there are critics that are working who are sexists…there are racists critics that are working, there are people who have inherent biases.”

Quinn Shephard is sure in her opinions, with feminist values at the core of her work. While diversity and representation continue to elude the film industry, Quinn sees how easy it is to commodify these concepts; “I don’t think anyone, myself included, wants to feel like they’re like a tick on a box for a company…because they feel like they are satisfying a diversity quota,” she calmly explains as we venture further into more controversial topics. But she also believes that if there’s an opportunity to diversify the media, and share stories of people who need their voices heard, then it’s an opportunity that should be taken; “And whether that’s commodification of diversity behind the camera, or whether it’s a genuine push for those things or a kind of a mixture of both which I think it is, then as long as we’re moving in a positive direction, I think that’s what matters..”

And with a graceful yet strong finishing note, she ends our long talk with bright hopes for the future of filmmaking in the next decade of her career. She even chastises me a little, slightly in good humor, and a little to make a statement that women, and minority filmmakers, aren’t just their gender or their race, but filmmakers who are just doing their jobs. “You know, as a female director, every interview you’re asked about what are the struggles that we face as a woman. And it would just be awesome if, in ten years, women didn’t have to be asked that all the time.”