With the unprecedented success of drag in pop culture, the art form rising from resistance to the front line of the queer movement, we look at the experience on an internal scale and navigate it through a greater path of self-discovery and love.

Related: Homecoming Queen: How Manila Luzon Is Bringing Filipino Pride To The World Stage

Back in college, I was introduced to this then little cult-favorite show you might have heard of, RuPaul’s Drag Race, by a dear friend and further encouraged by of course, my almost unhealthy Ohnotheydidnt habit on LiveJournal. (Clearly, I am jurassic.) In between sticking my nose in Political Science and English Literature books, lengthy, crammed papers, and all things in between, I would huddle on an empty station in the far end corner of the computer lab and watch episodes of this intriguing iteration of reality TV.

Quickly turning into a rabid fan, I pledged allegiance to the show, RuPaul, its quirky cast of characters (remember the pre-Michelle Visage pinch-hitter, Merle Ginsberg?) and naturally, the art of drag.

With a diverse assemblage of personalities, races and aesthetics, as well as unerring points-of-view, the audience would be schooled on the rigors of drag, apart from its obvious entertainment. Coloring the vaseline-filtered lens of a trial-budgeted show were OG queens such as Bebe Zahara Bennet, Shannel, Tammie Brown, Victoria “Porkchop” Parker, Nina Flowers, and Ongina, all of which have deeply been embedded in the recesses of my fairly impressionable mind.

I am no stranger to the concept of drag. In fact, my first traces back to Bugs Bunny dressing up as a female in order to sway his enemies or avoid the likes of Elmer Fudd and Yosemite Sam. As a child, I didn’t think anything of it. Sure, it felt odd, interesting even, but ruled by the pervading stereotypes of society, I just thought of it as a riot of funny. And then my parents, being the fairly liberal people that they are, popped in films such as To Wong Foo Thanks For Everything, Julie Newmar and The Birdcage on the VHS player during weekend movie nights.

More than a growing curiosity, being introduced to such ground-breaking and landmark films of its time, it sparked a slow build of wonder in my head, which was naturally followed by an internal conversation that sprang from innocent questions like: “Who are they?”, “What is it like to think like them?”, “Why are they doing this?”

It sounds pretty existential, but by not understanding what it really, truly was, and conversely, what it stood for, the spectacle gnawed at me until I decided to think none of it as a respectable form of art magnified by things like big hair, tarantula-like lashes, painted faces, and lots of feathers and sequins. But like many things that elicit such a reaction, it stays with you for longer than you care to admit.

MISUNDERSTAING IMPRESSION

Ironically, however, my first known brush with cosmetics wasn’t exactly a pretty picture. It was a particularly crisp and bright morning in the middle of June, and my half-asleep self was herded to the neighborhood salon where I was to be “dolled up” for my aunt’s wedding. I was a ring bearer and they figured it was necessary to pat a little powder on my face and smear lipstick on my lips. While my legs dangled and swung from the seat that was too big for me, they slicked a generous helping of gel on my hair and just as they twisted the tube of nude-colored lipstick, I bolted from the chair and ran to corner screaming, “Nooooo!”

Apart from it being unnecessary (come on, I was a child), I thought it was a stamp of being girly. And as every young boy would attest to this, it was well, ew. More than a child thing to say, something else bothered me: What would they think of me had they were successful in their bid to make me up?

You cannot put it past me as someone who was somewhere short of hitting the double digits in terms of age. I sure knew I was different, but not that way, I argued. But admittedly, there was something in me that wanted to know what it would feel like to have beauty things painted on my face. Yes, I was still caged by the presets of binary archetypes, but curiosity outweighed in to a certain degree.

As time went on, the self-prescribed inquisition never escaped me. It was along this point of the timeline that I had grown a penchant for the Spice Girls, Britney Spears, and would even look over my shoulder to check out the 80s style Barbie doll or nail salon set my sister got for Christmas. This isn’t to limit these strongholds as tell-tale signs, but it sure sparked an immense sense of joy and playful pretense when I got to sprinkle glitter on the plastic stick-on nails or repurpose the fashion of Barbie.

These sorts of things made me so happy, and yet I couldn’t fully express it, because this wasn’t what normal boys would play with, and so we were told. So, I kept it all to my introverted already misunderstood self, and made a workaround. Hey, even my Aladdin doll needed a much-needed makeover, too.

IT’S ALRIGHT

Aside from running my fingers along the spines of the dusty moss green encyclopedia set of my youth, I would sneak into the room of my parents and marvel at the organized set of nail polish of my mother. Everything about it spoke to me: the colors, the sparkle, the gloss. But again, it wasn’t a boy thing. So, when one time I got caught looking longingly at it, I just darted my gaze and hands at the nearest thing: my father’s current Tom Clancy read.

I’m pretty sure they noticed, but thought nothing of it—apart from the fact that it painted a silly smile on my face. So much so, one time I felt severely unwell and I had chosen to skip school, my mother woke me up and suggested she paint my pinky nail to cheer me up. Taken aback, I relented, trying so hard not to giggle at the luck I struck. “Just one,” she said, smiling as she carefully painted coats of a flesh tone three times apart on my right hand nail. “Thank you, Mama,” I said, looking at it closely and finally understanding that I was perhaps a little different than most boys.

And you know what, I didn’t feel bad. In fact, I quite liked it.

DRAG GENESIS

Time would further progress and my difference manifested itself well in atypical interests such as playing pretend on stage at the theater, enjoying the antics of Roderick Paulate in films like Bala at Lipistik, wearing old oversized office offshoots of my mother to school, and feeling a weird affinity for Ranma ½ or the manic villain in Powerpuff Girls, Him.

Thinking none of it as surface-level permutations of growing interests as a realized homosexual man, the dots finally connected and made sense when RuPaul’s Drag Race made a blip on my radar of pop culture. Sure, I’ve seen it on TV, film, sometimes also on stage, but finally I understood that this wasn’t a mere act of cross-dressing for laughs or gender-bending for the sake of entertainment. This was a defiance, a revolution to the pervading system that has pulled the brakes on progress for a long, long time. Rooted in politics and the personal, drag was challenging the norms of a generally unaware public. It wasn’t just a reality TV show, it was an education on gender, equality, and most importantly, humanity.

However, I saw it as just that then—a TV show appreciated at arm’s length. Sure, it was inspiring to see what was once a misunderstood underground form of resistance grow into the beloved art that it is today, but I never imagined myself actively participating in it other than never missing an episode, sometimes writing about it, spreading the good word to friends, and even supporting local drag acts. (What we have here is a gold mine of talent, I tell you.) I mean, yes, I would sometimes give in to the urge of wearing heels at a permissible office downtime and walk down the halls ala the supermodel of the 90s, but it wasn’t anything more than that.

All this would change once I started interfacing with strangers turned friends, and for some even, family, at the local bar, Nectar Nightclub that plays hosts to Poison Wednesdays and its popular project, Drag Cartel.

I would soon find the long drawn discussions turned discourse of drag and Drag Race frustrating, because there were large chunks of it I didn’t fully grasp in reality. I had the theory down pat, with so many tabs of literature saved on my laptop, but I wanted to know more. Scratch that, I wanted to feel more—even just once.

In an ironic twist of fate, one brought about by peer-pressure, a split-second gust of courage and the assurance of the most trusted people, I found myself sitting in a cold, mostly dark, barely finished space, lit only by the ring light jutting out in between my perch and the table in front. Neatly organized were stacks and rows of the latest, most covetable products from brands such as Fenty Beauty, Nars, Laura Mercier, MAC, and La Mer, all ready to be used for battle. Expertly wielding these weapons of mass beautification is makeup artist Anton Patdu, who then asks me: “You’re nervous ‘no?”

With playing cards firmly pressing down on my hair and my now colored nails digging through my palms, I look up and answer, “Very.”

Let’s put things into context: I had decided to finally go drag for the first time. Sure, it sounds like fun, but it also is nerve-wracking, especially for someone who detests having anything plastered on his face for long periods of time. If it weren’t for him and the constant coercion of my friends, I wouldn’t be sitting there wondering why I put myself in that situation, finally agreeing to have my face beat—that’s make me pretty in drag terms. “I’ll only do it if you will,” I dared him. “Game,” he fires back. Looks like there was no turning back now.

Let’s put things into context: I had decided to finally go drag for the first time. Sure, it sounds like fun, but it also is nerve-wracking, especially for someone who detests having anything plastered on his face for long periods of time. If it weren’t for him and the constant coercion of my friends, I wouldn’t be sitting there wondering why I put myself in that situation, finally agreeing to have my face beat—that’s make me pretty in drag terms. “I’ll only do it if you will,” I dared him. “Game,” he fires back. Looks like there was no turning back now.

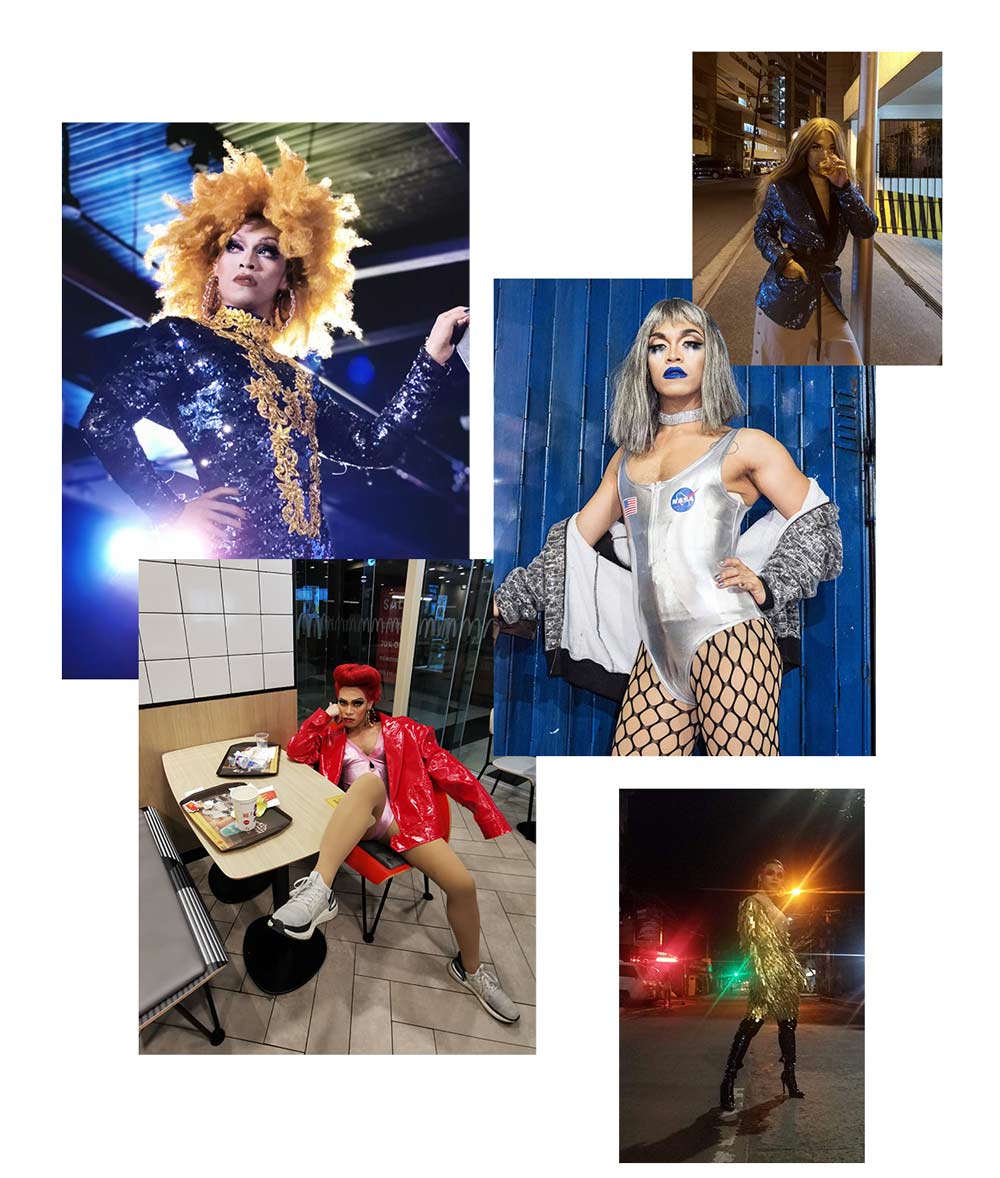

Almost two hours later, I turned to face the mirror, which I had totally avoided all the while, and finally saw someone else. “A woman,” we would often joke in the realm of Drag Race. Studying my face, I saw how my brows were now glued down and drawn over to mimic a judgmental arch, lids colored in with a swirl of vivid fuchsia and deep purple, two (or was it three?) stacks of lashes were firmly placed on the top and bottom line, and an ombre of pink and red tumbled on my exaggerated lips. With a twice cinched waist, a neat and tight tuck (read: genitals), layers of stockings and fishnets to boot, the finishing piece was crowned on my head—a striking silver wig fashioned in a nonchalant long bob by hairstylist Mong Amado.

Look, I didn’t necessarily feel like a different person. What I felt was that I became a hyper-realized extension of myself, taking on a persona of Miss Kiki (last name: Kensington, if you’re feeling polite), an anachronistic diva perpetually stuck in the colorful era of the 80s. With a wash of excitement, I ran and slid on the chrome thigh-high boots, where a wash of power and an abundance of confidence draped over me. I knew I had to walk out to curious stares and unforgiving judgments, but I couldn’t care less. For once in my grown life, I actually felt uninhibited; I felt free.

THE GOSPEL TRUTH

The night would progress into a blur of lights and other forms of drag (ultra-feminine, avant-garde, spooky, campy, etc.) and varying shrieks of “Oh my god! Is that you?!” where it ended in a body that ached from all the hours of standing and dancing in heels, as well as breaking in this newfound sense of liberation. It was exhausting, and it still is, as I continue to my enthusiasm for drag every once in a while my alter ego climbs out of the dusty caverns of semi-retirement, but in the span of time I have been immersing myself in this first-hand experience, I am slowly beginning to understand what it really truly is for different drag queens—a term I do not want to call myself, because I feel that is the attainment and commitment of the highest order.

For some, it is a hobby or passing passion, for others it is an act of protest for whatever reason they see fit (gender, expression and social standards), which are all in itself admirable. But for others, it is their way of life, their livelihood and salvation, literally carrying them through some of the deepest, darkest points. These are the true queens, in my opinion, as they persist night after night with a craft that is still not fully understood beyond lip syncs, reads (a witty, no-holds-barred type of impertinence), splits, and death drops. It is their way of life, the lifeline that dips and dives at every thumping and throbbing of the bass at night club or at every engagement that requires their larger-than-life personas. A gag for others and an escape for some, it is the very thing they run to for survival, giving them the space to set spirits, theirs and yours, on fire.

There is still a lot to learn from the art of drag both as an audience and someone who occasionally dips his toes and twirls to the tune of Oops I Did It Again by Britney Spears, but what is crystal at this point of the immersion is that it really allows you to look into yourself to fully comprehend every high and low of your entire being. Being in drag isn’t all fun and games, as it also compels one to an existential exercise of exploring dichotomies such as the obvious masculinity and femininity, rage and restraint, and passion and purpose. It may seem superficial, but the act of getting into the whole nine yards and much more of drag forces you to discover and appreciate who you really are, which in turn makes you a more effective performer or entertainer, and most importantly, a well-informed and feeling human being.

As for me, well, let’s say I found more of myself. It isn’t just the glamour and glitter of it all. I mean, try standing and dancing in heels the whole night through, getting the wig tugged, and having to skip peeing altogether. All sass aside, drag posits a possibility of uninhibited and unapologetic freedom, one that accords me the confidence to go balls to the wall in pride, afford me the exhale to not give a damn, and most importantly, allows me to be who all I can be.

RuPaul himself says it best at the end of every episode: “If you can’t love yourself, how in the hell are you gonna love somebody else?” It is gospel truth at this point whether you are a fan of drag or not. It is a cornerstone of life itself that perhaps was lost along the way of evolution. But all waylaid things get found eventually, and as it stands, we are at a glorious time of our lives where pop culture and the greater value of humanity meet a colorful compromise. Yes, we still have much of a distance to go in order for the preferences and perceptions to meet at an equilibrium, but who would have thought that all it would take for the movement to break more ground was a collective of men in wigs and heels? No one saw that coming, but boy are we thankful to be making great strides in the self-discovery of life, love, and liberty. Now, can I get an amen?